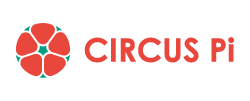

Let’s return to the code. During the sprite creation process, we placed our designed sprite into a “Variable.” Just like our understanding of the box metaphor: once the sprite is stored, the data won’t change unless we modify it.

You can see that this variable has a name. To avoid picking up the wrong “box” when passing variables around, we give it a name. By default, the program names it “mySprite.”

We can understand that the variable “mySprite” is equivalent to the “Sprite (Orange Dinosaur).” So, when we set the position of “mySprite” or use the controller to move “mySprite,” we are effectively controlling the “Sprite (Orange Dinosaur).”

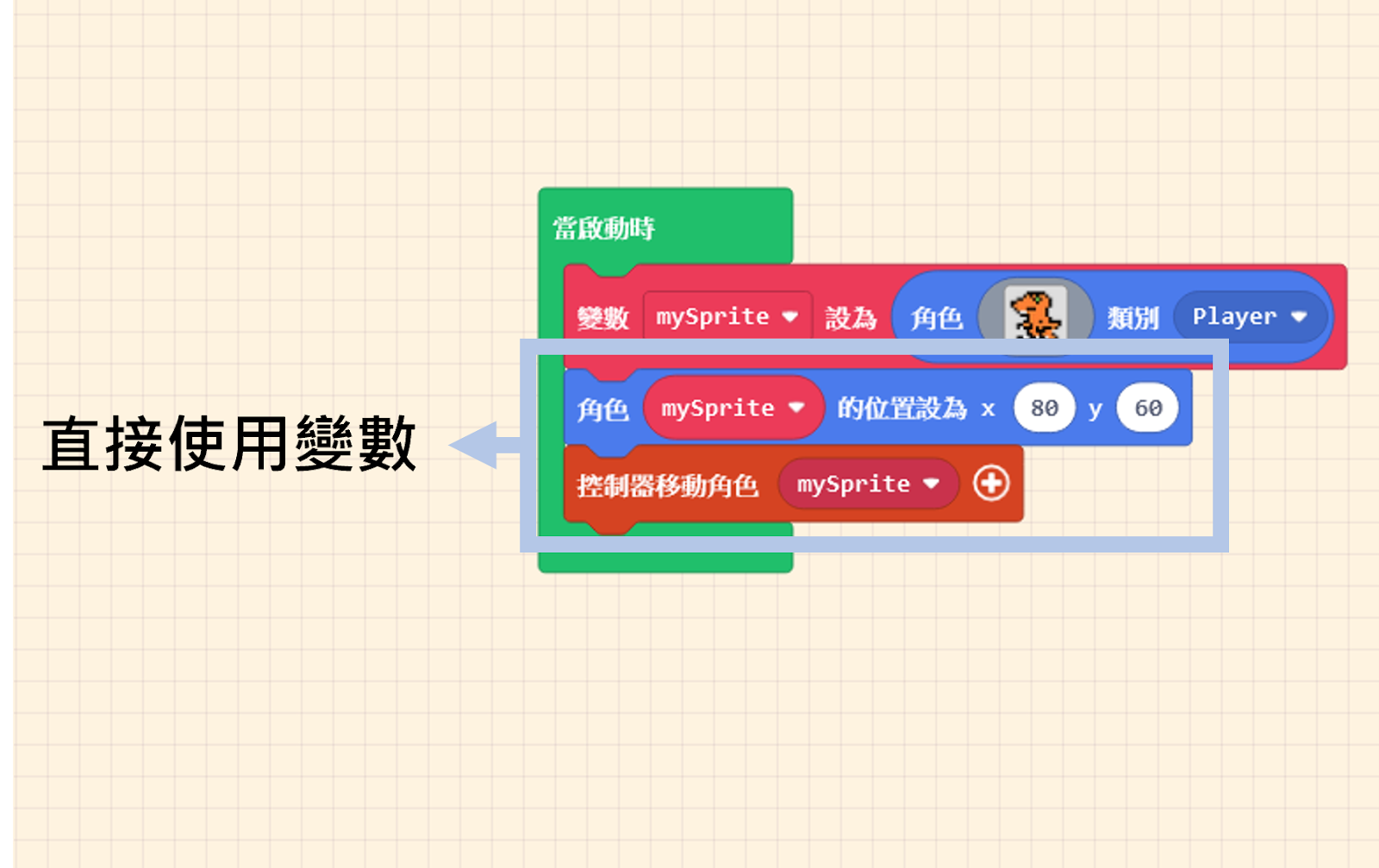

At this point, quick thinkers might ask: “Why can’t I just do this?” (referring to using the “create sprite” block directly in every command).

If you write the code as shown in the hypothetical image above, running it will reveal a surprise: there are two sprites! One is controllable, and the other is not.

This is because the block “sprite [ ] of kind (Player)” essentially means “Create a NEW Sprite.” If you use this block again in a movement command, you are creating a second sprite—one positioned at (x: 80, y: 60), and another separate one that moves with the controller. This is why you see a “shadow clone” (duplicate) in the Game Simulator.

Although creating a variable seems like an extra step, think of it this way: the named variable is like giving your sprite a specific name. When you want to control it, you call it by its name.

Click on the variable name within the block, and select “Rename variable…” from the dropdown menu to give it a new name.